The Real Reason Why We Travel Even When It’s Hard–And How to Bring That into the Rest of Your Freelance Work

There is an important part of doing something new that we always seem to forget in the excitement of novelty.

Our need for novelty has been well documented in pretty much anything you read today about the technology addiction pandemic.

Whenever that little ding of a notification or flash of a new email appears on our screens, we get a hit of the chemical dopamine, the same chemical associated with eating your favorite food, having sex, and getting high on cocaine.

And when the extent of the new thing in your life is equally as momentary–scanning the latest shutdown headline, trying a new flavor of ice cream, or checking an editor’s tweet calling for pitches–the let down if it doesn’t turn out as planned is short-lived and typically doesn’t cause you to ask bigger questions about why you are doing what you’re doing and if it’s really a good idea and whether you should just chuck it all and stop right now.

But when the new thing is bigger, like, say, trying to become a freelance travel writer, and what you’ve invested in that new thing is on a scale of months or years, when you hit a snag, the reaction can be very different.

In last week’s Freelance Travel Writing Bootcamp, we hit this effect on Wednesday, after a full day of classes on Monday followed up two days of morning classes, afternoon tours, and evening debriefs on what usable article ideas the day’s outings had turned up, the consensus in the evening debrief was very simple: “this sh*t is hard.”

I don’t think anyone necessarily expected it to be easy to develop the basics of all of the skills you need to be a functioning full-time travel writer in one week when they signed up.

But until that third day, the novelty juice was keeping the difficulty at least slightly lower in the general consciousness than the excitement.

This happens to all of us at some point when we travel. I’m sure you can remember such a time well. Perhaps a site wasn’t all you expected it to be. Or the hotel you finally checked into at the end of a long day was more of a respite for bugs than the relaxing temporary home base you were looking for. Maybe a delay marred your well-laid plans for what you could see in the time you had in a once-in-a-lifetime destination.

When it happens in your travels, those moments when sh*t get hard, tend to be ones where you have no choice but to move through the moment to get to the other side of the difficulty. You have to get home somehow, right?

But in building our travel writing careers, that no-choice situation so rarely exists. You can always (God forbid) just not turn in an assignment you’re stuck on. Or, more frequently, not send a pitch you’re not sure is a fit–or stop writing it after the first line, if you even get that far.

These situations often make me think of Don George, editor of the Lonely Planet travel anthologies, who was pegged by a friend and fellow author, Jeff Greenwald, as never having this issue in an interview coinciding with the launch of Don’s short story collection, The Way of Wanderlust:

Jeff: I want to talk about the threshold of inhibition. Everywhere I’ve been with you, you cross it. How do you feel at home anywhere in the world?

Don: Every time I leave by inhibitions behind, something great happens, and it reinforces the value of doing that. Now, 40 years later, I feel like I would be doing a disservice to myself, my work, and my writing if I didn’t do it. The rewards are so incredibly huge.

I love that Jeff used “inhibition” here, because, unlike fear, which has more of a potential negative reflection on one’s self, I find that inhibition can encompass most things that stop us from doing things in a less judgemental-sounding way.

Merriam Webster defines it as:

: an inner impediment to free activity, expression, or functioning: such asa : a mental process imposing restraint upon behavior or another mental process (such as a desire)

One story of Don’s in particular, the one that concludes his collection of stories The Way of Wanderlust and originally appeared in the first year of stories in the Words & Wanderlust section he edits on BBC travel, to me has always been the epitome of this idea that “something great” happens when you cross that threshold.

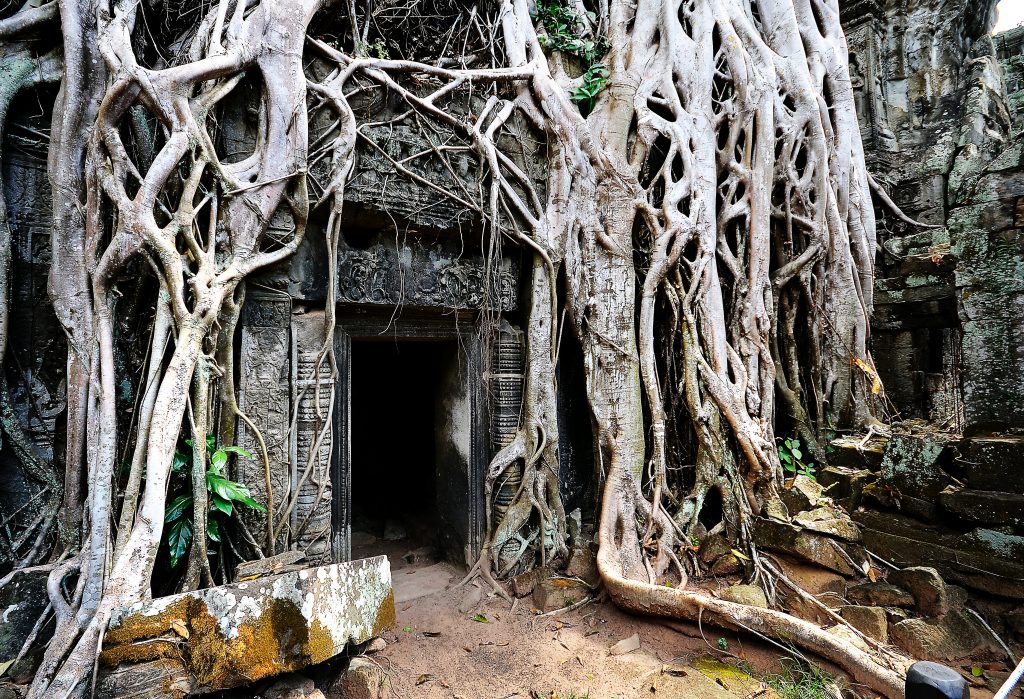

It’s a long piece about finally going to Cambodia, a place he had dreamed of visiting since seeing Siem Reap in National Geographic as a child, but it glances past most of the time in that cultural capital to focus on a rural village when he decided, with very little background information, to do a homestay.

After finally finding his new home and getting settled in, he suddenly:

“felt utterly overwhelmed: What had I gotten myself into? My hosts didn’t speak English. I was cut off entirely from the outside world. The roads were a muddy mess. I had no means of transportation and no idea what I was going to do for the next three days. Sweat poured down my face.

Was there a shower, or even running water? And what about the toilet — where, and what, was that? What had I been thinking when I booked three nights here?

It took all my energy simply to lift my mosquito net and crawl into its cocoon.”

Three days and several private tours of temples so off-road most locals couldn’t even find them if they tried later, Don found himself in an impromptu gathering to commemorate his surprise visit of Thai and Cambodian soldiers guarding a section of border with a temple marked with shells and gunshot marks from border skirmishes just a few years earlier.

After Don’s words of thanks for the honor had been translated to the group,

“quite unexpectedly, a very young-looking soldier at the end of the table got up and began to speak. His voice quavered at first, but as he continued to speak, the words flowed out of him with a pure passion.

‘I am just a simple soldier,’ Mr Kim translated. ‘I have not travelled far or seen much in my life. But today is a very special day for me.’

He looked directly at me. ‘Our honoured guest is the first foreigner I have ever seen in my life, the first foreigner I have ever met. I am so excited and happy to have met you and talked with you. I cannot quite express what this means to my life. This makes me think how big the world is, and gives me a kind of hope. Please when you go back to your village, tell the people about the soldiers you met at Ta Krabey. And tell them about the peace you found here. I will never forget this day for the rest of my life.'”

One of the reasons that we do as much as we do in our Freelance Travel Writing Bootcamp is so that folks don’t just walk away with the hard parts. They leave with a polished pitch, a completed story the likes of which would appear in a $1/word outlet that they wrote on a tight deadline, and a notebook teaming with story ideas.

Even though it was difficult at the time, like Don’s amazing experience in Cambodia, they have left with things both tangible and intangible that make it feel like the hard parts were worth it.

That mental muscle that Don has so well toned–the strength of surety that discomfort and difficulty will lead to something great you could never have otherwise–is like any muscle.

You have to build it up with practice, and keep it strong.

We can’t all go off into the internet-less portions of rural Cambodia tomorrow and have this experience. But there are easier, closer to home ways to build yourself up in this way.

The Artist’s Way, the tome that gave us the concept of morning pages and countless outpourings of creativity that have shaped many parts of our cultural and literary landscape today, from everything Tim Ferriss to Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love and Big Magic, prescribes the “Artist’s Date,” time for yourself once a week to do something enchanting, like a visit to a gallery or museum, but particularly any place where a new experience might be possible.

What small (or large) thing can you do this week to find and build your confidence that there is always something great on the other side of the difficult parts of your freelance writing journey?